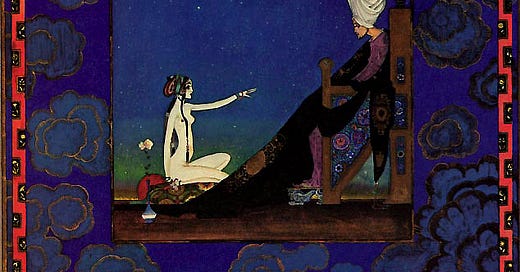

Who has the power? The storyteller or the Sultan who’s sworn to behead the virgin at dawn?

It would be too glib—if not downright dangerous—to say the storyteller holds the power, when we know full well that real-world Sultans (and their analogues) are notorious for ignoring some storytellers and favoring others, and that the storytellers who try to speak truth to power often do so with disastrous personal consequences.

Perhaps I’m asking the wrong question, then. It’s not ‘who is more powerful,’ but ‘where does power reside?’ In offices and institutions, of course—that’s how Sultans become fearsome—but also in stories, which, as far as I can tell, humans are constantly inventing, privately or publicly, for entertainment, to solve problems, or maybe because we just can’t help ourselves. We wake up and get out of bed, and the Inner Narrator starts up about how Our Hero’s had a stiff back ever since cleaning the garage last weekend, and how that’s going to make for an achy bike-ride tomorrow afternoon, and maybe Our Hero won’t be able to ride at all and will have to do something else entirely. Awake five minutes and already there’s a narrative forming with a little bit of plot (no one ever said that every story was exciting, you know!) around a grumpy protagonist who needs her coffee before the next chapter.

Stories are a huge part of what is passed down to us as children. We live inside of the stories adults tell us about the world, about themselves, about ourselves and why we’re here, how we happened to arrive here. As a kid, you read fairy tales, maybe, fables and legends and folktales, most of them cautionary, many of them deliberately shaped for children, so it’s easy to imagine yourself as the protagonist. Those stories as you read or listen to them become your stories, as they’re meant to, and they guide you in the manners and morals of survival in a largely unfamiliar world. Truly, as a young child, the world you encounter every day is hardly less menacing and strange than the Scandinavian forests of Anderson’s tales or the Bavarian forests of the Grimms. Even the Howling Desert and the High Veldt of Kipling’s Just-So Stories seemed as probable and as foreign in equal measure as the far corners of your own back yard.

For quite a long time, you’re held still in the magic spell of someone else’s telling. Dawn breaks and you wake to the woven world of the tale again and again. In your own mind, you’re the princess, you’re the orphan in the woods whose breadcrumb-trail has been gobbled up by critters, you’re Thumbelina, you’re the valiant little tailor, you’re Faithful John. In the daytime of other people’s telling, you’re the quiet one, the smart one, the shy one, the lazy one. You’re the one who eats too much, the crybaby, the one who throws like a girl. The only way to stop being a character in someone else’s story is to take over the telling, become your own Scheherezade.

What did the little girl who saw the transparent woman learn? What could that encounter have taught her about the world? What inherited story did that one replace or amend? Did she learn where she came from? What she was made of or meant for?

Not then, for she did not tell the story. The image of the plastic woman baring her insides would form a droplet, a seed, or a pill; it would lodge in a crevice of the girl’s mind for decades, dormant. Or was it? Perhaps it sent out rootlets, securing its place in the soil before sending up the shoot of a story. We’ll have to dig around to see about that.

Not long ago, my parents and I were talking, doing that sort of storytelling that families do to remind themselves of who they are together. I referred to my birth, how it happened nine months after their marriage. Casually, my mother said, “well, you know, sometimes birth control doesn’t work.” It was the first I’d heard—the first I remembered hearing, at least—that my conception was accidental rather than part of how they had intended to live those days and months at the start of their marriage. My mother didn’t mean to shock me (I think?). By now, fifty-four years after the fact, she may have believed I already knew that little factoid, that I had long known. But for me, it felt as if I’d been gone for a while from the now of my life’s narrative, a time-traveler off gallivanting, and had arrived back in a present that appeared the same as ever, but turned out not to be the story I’d thought I’d lived.

The thing about the story of one’s life is that it doesn’t strictly belong to any single person. My story starts before I am aware of myself, and by the time I discover I can be its author and take over the telling, I’m deep inside a forest of someone else’s dreams and fears, surprised to run into a wolf whose ill intent is both unfathomable and plotted to be inevitable. Why me, and why a wolf? Why not a fairy or a fox or a bunny, please? Why not a faun?

How does the sister in the Grimms’ story of the six swan-brothers survive to break the spell and turn them back to men when, to comply with the magic’s demands, she can’t speak a word on her own behalf? She endures, but just barely. She is captured, made a wife, made a mother, her children are stolen from her, she is misrepresented, condemned, nearly burned at the stake. In the stories others tell in the hollow room of her silence, she becomes two people, as different as night and day, a gentle mother and a twisted cannibal. Neither is fully true; neither is her story. The Grimms’ tale ends when she fulfills the terms of the charm and can break her silence. She takes over the telling. And so she is redeemed (though her immense suffering cannot be reversed), the terrible step-mother is punished terribly, and one brother is left asymmetrical, one-armed, one-winged, a visible reminder of the deep toll silence exacts from the powerless.